The April 21, 2008 issue of Newsweek (on newsstands Monday, April 14), "Splitsville," provides an intimate look at the ways divorce evolved from something shocking to a fact of American life. Senior Editor David Jefferson interviews his high-school classmates who tell their sides of growing up as part of "Divorce Generation." Plus: how a recession may improve air travel; Barack Obama's bottom-up foreign-policy experience; what's really in your kids' videogames and Portishead on their long-awaited third album. (PRNewsFoto/NEWSWEEK) NEW YORK, NY UNITED STATES 04/13/2008

13 Apr 2008 16:31 Africa/Lagos

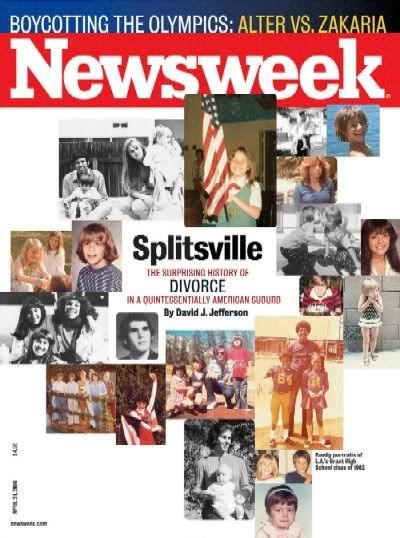

NEWSWEEK Cover: Splitsville

The 'Divorce Generation' Grows up and Reflects on the 'Ultimate Threat to Innocence'

Many From the Class of 1982 Still Deal With the Impact Their Parents' Decisions had on Them

NEW YORK, April 13 /PRNewswire/ --

During the 1950's marriage was the most powerful social force. After California Governor Ronald Reagan's 1969, "no- fault" divorce law allowed couples to end a marriage by declaring "irreconcilable differences," divorce became the most powerful social force. Divorce evolved from something shocking, even shameful, into a routine fact of American life. Its effects, however, are no less profound.

(Photo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20080413/NYSU001 )

In the April 21 Newsweek cover "Splitsville" (on newsstands Monday, April 14), Senior Editor David J. Jefferson and his classmates from Ulysses S. Grant High School class of '82 tell their sides of growing up in L.A.'s San Fernando Valley as part of "Divorce Generation." In a series of intimate interviews with former classmates, Jefferson examines how divorce changed the lives of the children who lived through the explosion of the myth of the nuclear family, the first for which divorce was just another part of growing up. These interviews show how living through divorce shaped their lives, influenced their relationships and changed their expectations of commitment.

"Although I grew up a few blocks from the 'Brady Bunch' house, the similarity between that TV-family's tract-rancher and the ones where my friends and I lived pretty much ended at the front door," Jefferson writes. "In the real Valley of the 1970s, families weren't coming together. They were coming apart. We were the 'Divorce Generation,' latchkey kids raised with after-school specials about broken families and 'Kramer vs. Kramer,' the 1979 best-picture winner that left kids worrying that their parents would be the next to divorce. Our parents couldn't seem to make marriage stick, and neither could our pop icons: Sonny and Cher, Farrah Fawcett and Lee Majors, the saccharine Swedes from Abba, all splitsville."

By the late '70s the women's rights movement had opened workplace doors to mothers-more than half of American women were employed, compared with just 38 percent in 1960-and that, in turn, made divorce a viable option for many wives who would have stayed in lousy marriages for economic reasons. By the time Jefferson and his friends entered their senior year of high school, divorce rates had soared to their highest level ever, with 5.3 per 1,000 people getting divorced each year, more than double the rate in the 1950s.

"Researchers have churned out all sorts of depressing statistics about the impact of divorce. Each year, about 1 million children watch their parents split, triple the number in the 50s. These children are twice as likely as their peers to get divorced themselves and more likely to have mental-health problems, studies show," Jefferson writes. "When we were growing up, divorce loomed as the ultimate threat to innocence, but now it just seems like another part of adult life ... What I wanted to know was how divorce had affected our class president and Miss Congeniality, the stoners and the valedictorian. Did it leave them with emotional scars that never healed, or did they go on to lead 'normal' lives? Did they wind up in divorce court, or did they achieve the domestic bliss their parents had sought in suburbia? I decided to open my yearbook, pick up the phone, and find out."

After reuniting with his friends, Jefferson found that despite the dire predictions, a surprising number of Grant alums wound up in solid marriages. Jefferson's best friend, Chris Kohnhorst, who he had met in the fifth grade and the first kid he can remember encountering whose parents were divorced, got married 15 years ago and is still happily married. Chris's life since his parents' divorce, "has been shaped to a tremendous degree by the goal of avoiding divorce as an adult at all costs," says Kohnhorst. Jefferson also found that the urge to get and stay married is stronger in his classmates' generation than the urge to get divorced was in their parents'. "Every honest couple will tell you that it's hard sometimes," says classmate Josh Gruenberg, who now lives in San Diego with his wife and three kids. "You have to compromise, and it takes work," says Ruth Kreusch, who's been married for nearly 17 years and has three kids. David Selig says divorce isn't as prominent in his social circle now as it was when he was growing up -- though his circle is admittedly smaller, since he's become much less social than he was in high school. "My wife and I would rather spend time with each other and our five rescue dogs than just about anybody else," says David, who's been with his wife for 18 years.

Others, however, were not able to avoid divorce. One ugly side effect, according to research, is that divorce can be passed from generation to generation, like some kind of genetic defect, with children of divorce becoming divorces themselves. Tonju Francois married when she was 28 and got divorced six years later, in part, because her husband didn't want to have kids (he already had children from a prior marriage). "I loved being married, and it devastated me when it ended," she says. Elyse Oliver got married when she was 25 and divorced four years later. "I guess I just didn't know what to do in a relationship," she says.

Other classmates wound up marrying much later in life than their parents did (that's in line with the research, which shows that children of divorce tend to marry either later than their peers, or much earlier, in their teens). Lisa Cohen, waited until she was 35. "This generation grew up with such a massive culture of divorce that I think there was an effort to make better choices about who we married," says Cohen, whose parents wed in their 20s. "I was pretty clear on the fact that I didn't just want to marry someone for how good he looked on paper or how crazy in love we were."

Jefferson writes that "Despite the complications and the collateral damage, my friends from Grant High's class of '82 seem to agree that the divorces in their lives -- both their parents' and their own -- were probably for the best. Most don't think ill of their parents for having split up. "As a child I felt like I was a victim of my circumstances, a victim of the divorce," says Deborah Cronin. "But as an adult I learned that my parents were just two people who met each other, fell in love, had children, and it didn't work out. They were 18 and 19 years old when they met. They were young kids having kids." It seems that along with the crow's feet and expanding waistlines of middle age, my classmates and I have acquired an acceptance of our parents and their life choices. Some of us have even found healing. "My parents were good people," says Francois. "And good people get divorced, too."

(Read cover story at www.Newsweek.com)

URL: Complete coverage

Photo: NewsCom: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20080413/NYSU001

AP Archive: http://photoarchive.ap.org/

AP PhotoExpress Network: PRN1

PRN Photo Desk, photodesk@prnewswire.com

Source: Newsweek

CONTACT: Brenda Velez of Newsweek, +1-212-445-4078

Web site: Newsweek

http://www.newsweek.com/id/131838

N.B:

For more inquiry on Divorce, contact me.

Please, note that I am anti-divorce, except in cases where life is in danger.

No comments:

Post a Comment